What You Need to Know About Premature Babies

Parts of pregnancy are predictable: crazy pickle-and-peanut butter cravings, morning sickness, that nagging bladder. But most of pregnancy is not so predictable—and that includes the possibility of a premature baby determined to come out ahead of schedule. The best way to calm your worries about such unexpected events? Be as informed as possible. We’ve rounded up the important expert advice to make that happen.

A normal pregnancy typically lasts about 40 weeks. A premature baby, sometimes referred to as a “preemie,” is a baby born before the end of the 37th week of pregnancy, according to the World Health Organization. About 1 in 10 births in the US are premature.

The designation comes in degrees: A baby born at 28 weeks or less is defined as “extremely preterm”; a baby born between weeks 28 and 32 is “very preterm”; and a baby born between weeks 32 and 37 is “moderate to late” preterm.

One of the most frustrating things about premature birth is that, in many cases, doctors are often not able to explain why a healthy woman has a premature baby, says Paul Jarris, MD, chief medical officer at the March of Dimes.

What doctors do know, though, is that in general, premature births have been associated with a spectrum of maternal conditions, including stress, infections, diabetes and high blood pressure. Premature babies have also been linked to pregnancies that occur less than a year after a previous baby, as well as to moms who are underweight. Most important, premature babies have been linked to moms who smoke. That risk goes down if women stop smoking even late in pregnancy, says Emily DeFranco, DO, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

Besides avoiding cigarettes (and—obviously!—drugs and alcohol while pregnant, there are also plenty of other things you can do to raise your odds of having a healthy full-term baby: This includes being physically active at a level that’s comfortable for you; eating nutritious foods, getting your sleep and finding healthy ways to manage stress. You know, the usual.

What also helps: making an appointment with a pregnancy care provider as soon as you know you’re pregnant and going into that visit knowing your health history, Jarris advises. If you’ve been pregnant before, were there any complications the first time? Do you have diabetes or high blood pressure? Did your mother deliver prematurely? “If your mom had a premature birth, you’re more likely to, so it’s good to know that,” Jarris says. Your doctor can also manage other conditions that might increase your chances of having a premature baby.

However, there’s no way to guarantee a full-term baby. “Even if you do everything that you can do, you still may have a preterm birth,” says Jarris. And while it’s only natural for mothers of preemies to question what they could have done differently, Jarris says, they shouldn’t. Instead, mothers should focus on the present and do the best they can for the premature baby. “If she’s done what she can during the pregnancy [by staying] as healthy as possible and has a preterm birth, there’s probably nothing she could have done,” Jarris says.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about a third (36 percent) of all infant deaths were because of preterm-related causes in 2013. Premature birth is known to be the leading cause of death in children under the age of 5 around the world.

However, it’s not so easy to know how many preemie babies survive. It depends on the child, how early she was born, the specific conditions she suffers from and the medical facilities available to her. Her chances for survival increase with every week she is able to stay alive. In a 2012 JAMA study of more than 34,600 premature babies born between 1993 and 2012, the survival rate of the most vulnerable infants— those born between 22 and 28 weeks—grew from 70 percent to 79 percent. The authors of the JAMA study suggests that better infection control in hospitals and more effective treatment given to the mother before birth are important factors in the improved survival rates in recent years.

According to the Quint Boenker Preemie Survival Foundation, premature babies born 32 weeks onward are, for the most part, expected to survive, thanks to medical technology. But with the right care, even the smallest premature babies can grow up to be strong, healthy, happy adults. The world’s youngest premature baby to survive is James Elgin Gill, who was born at 21 weeks 5 days in 1988. Given his extremely early arrival, he wasn’t expected to live, but he wound up heading off to college as a healthy teenager. Just shy of the record, Amilia Tayor was born at 21 weeks 6 days in 2006—and aside from mild osteopenia, she’s a perfectly healthy girl.

Care for a premature baby actually happens when baby is still in the hospital, where she’ll be placed either in a special nursery or in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Jarris advises moms to ask questions, understand what’s going on and make sure providers take the time to explain to her and her significant other what’s actually happening with baby and how they can help.

Just as important, mom should help baby know that she’s there for him. These tips for caring for a premature baby are important in the NICU as much as they are at home.

• Bring baby a little piece of cloth that carries your scent (sleep with it the night before). Place your hand on baby so she can smell you and feel your touch, and read or talk to her. “The baby can probably recognize your voice from when the baby was inside,” Jarris says.

• Talk to the hospital about pumping and having baby receive your milk. This might involve feeding through a tube or tiny cup or bottle.

• Hold baby skin-to-skin as soon as possible “That helps calm the baby, helps the baby attach and improves his outcomes greatly,” Jarris says.

• Take care of yourself. For instance, make an appointment with your doctor for a postpartum checkup, rest when you can, eat healthy, tell friends and family how they can support you and reach out to support groups where you can share your concerns with other members.

Cheryl Cooperstein, who gave birth to her daughter at 31 weeks (and a son at full-term before that), also wants mothers to know that they shouldn’t feel they need to be by baby’s bedside 24/7. “Take care of yourself and your other kids,” she says.

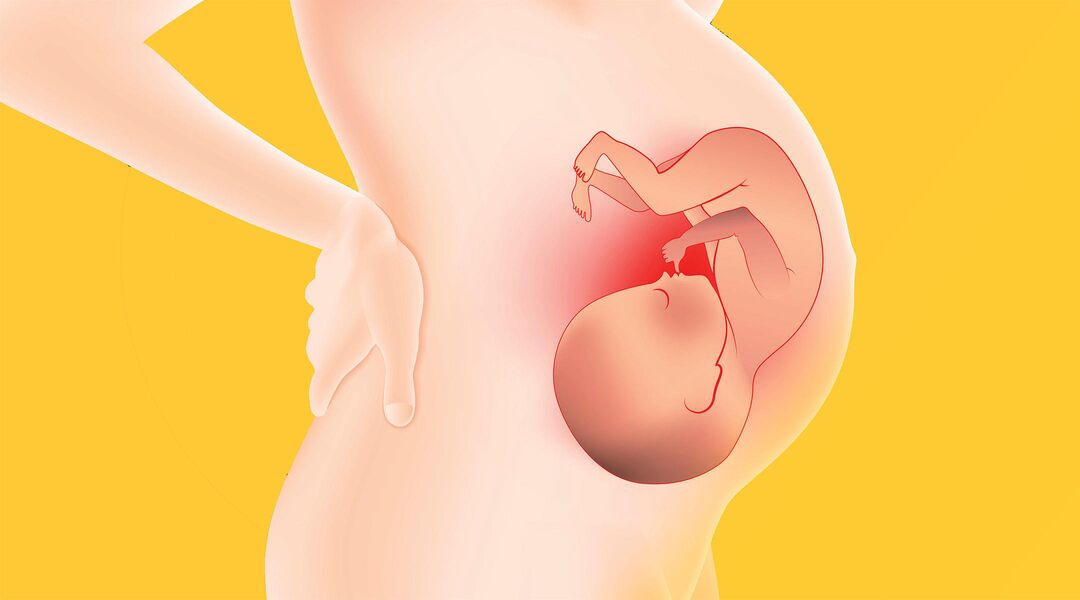

A lot of things happen in the mother’s belly during those final weeks of pregnancy. Baby’s brain and lungs develop more fully and so does her liver. It’s to be expected that premature babies risk facing challenges not just in those early days of life but also possibly after that. Those challenges may be severe for some kids but barely perceptible, perhaps even nonexistent, in others. It depends on the child and her treatment after birth, as well as how early she was born. Here are a few common risks premature babies may face:

- Breathing difficulties (such as asthma)

- Feeding difficulties

- Neurological disorders, such as cerebral palsy

- Developmental delays

- Vision problems (such as crossed eyes, color blindness or, in severe cases, vision loss)

- Hearing impairment

Parents can “adjust” baby’s age to get an idea of how she’s doing developmentally by taking into account her official birth date and her estimated due date. To calculate baby’s “corrected age,” the American Academy of Pediatrics says to subtract the number of weeks baby was preterm from his actual age in weeks. So, for example, if baby was born at 28 weeks, he was 12 weeks premature. If he’s now 6 months old, his corrected age is 24 weeks. While the early months may be rocky, eventually otherwise healthy premature babies tend to start catching up to their peers around age 2. What’s most important, though, is making sure your child is progressing in the right direction.

As a mom of a premature baby, Cooperstein discovered you need to trust your instincts—and guidebooks, with all their typical timelines, aren’t necessarily helpful; preemie baby development happens on it’s own schedule. Cooperstein’s child took her first steps at 16 months—half a year later than her son, who was taking steps at 10 months old. But running and climbing quickly followed. What’s more, Cooperstein worried her daughter wasn’t making all the sounds she needed to by her second birthday. But then? “A month before, she came out speaking in full, complex sentences.” At 22 months old, her baby was wearing 18-month clothes that were “huge” for her, Cooperstein recalled. Today that tiny baby is “a precocious, bright, curious, active, loving, chatty, typical 2-and-a-half-year-old”—and one that wears a size 4T or 5T shirt and 3T pants, at that!

Published October 2017

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.