How (and When) to Tell Your Child They’re Adopted

Telling a young child they’re adopted may sound earth-shattering, but in reality, this should be a no-drama moment. It’s really just about telling them the truth. “It’s a parent’s job to help a child understand their history,” says Joni Mantell, LCSW, a psychotherapist and director of the Infertility & Adoption Counseling Center in New York City. “Parents may find this to be difficult for various reasons—fears about how the child will feel, or anxiety that the child’s feelings towards them will change.” But your trepidations shouldn’t stop you from revealing this important life information. In fact, in most instances, the earlier you share, the better. Below, some tips to help make this ongoing dialogue easier on you and your little one.

No time like the present. Even if your child is an infant or toddler, you’ll want to start this conversation right away. Studies show that sharing this information early on (even if your little one may not entirely understand it) helps them feel more settled and satisfied later in life. On the other hand, waiting too long to divulge this info can lead to more psychological distress and feelings of anger, betrayal, depression and anxiety. “Every child wants, wishes and longs to belong to a unified family,” says Fran Walfish, a Beverly Hills-based family and relationship psychotherapist and author of The Self-Aware Parent. “Just like divorce and the breakup of the family unit is traumatic, so is the revelation that you’re an adopted child when your adopted parents made the mistake of not telling you at a very young age. Worse yet is the accidental discovery of this information.”

In other words, don’t wait, and be forthcoming. “Parents shouldn’t give in to the wish to delay these conversations,” Mantell says. “Telling young children some basics so they always know they were adopted, before they know what adopted means, is easiest for both child and parent.”

Procrastination may save you some stress in the moment, but delaying the inevitable ultimately backfires. What’s more, talking about it when your child is still very young gives you bonus practice time to overcome any awkwardness, so that future conversations will feel less clumsy and more constructive.

There’s a lot of confusing language that comes up around adoption. Phrases like “born in my heart” are said with care and affection but can be taken literally by young kids. Keep your initial story simple: Your child was born to other parents, but they couldn’t take care of them. You wanted to become their family—and so you did. This rudimentary vocabulary lesson and basic truth can serve as the foundation for later conversations.

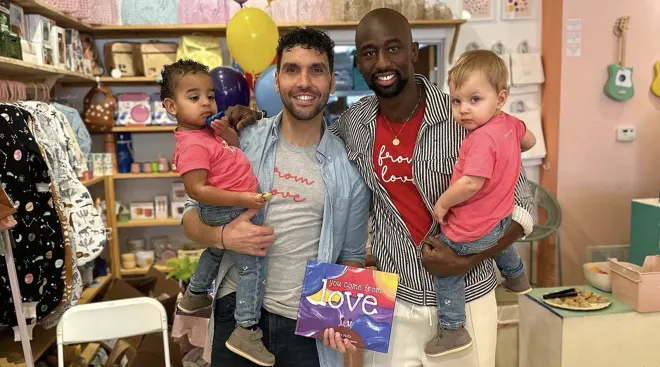

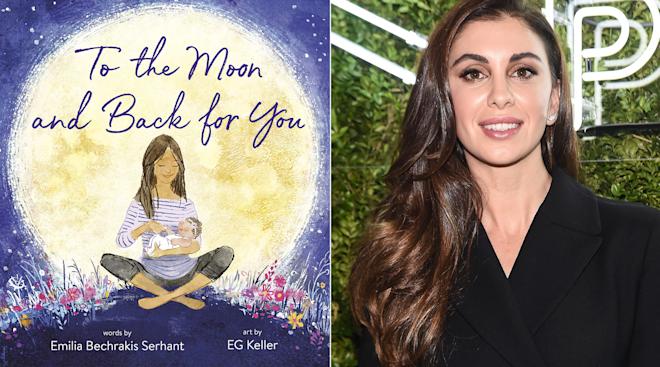

Broaching the subject on your own can feel overwhelming. If you’re having trouble finding the right words, check out a few picture books about adoption. Todd Parr’s We Belong Together and Keiko Kazsa’s A Mother for Choco are two great options that can help you get the conversation started. Snuggle up and read together; when you close the book, you (and your toddler) may feel ready to open up.

Your instinct might tell you to focus on your relationship with your child, but leaving the birth family out of the conversation entirely can actually create further confusion about how they ended up here. Mention their birth parents in the context of their adoption story—and if you know their names and are in an open adoption, share this information as well.

“You can use birth parents’ first names or any term you prefer with younger children, and introduce the term ‘birth mother’ when the concept of birth is introduced,” Mantell says. “Using the birth mom’s first name helps parents get used to talking about the birth family and may be less confusing to children who associate mother and father with their daily parents.” And while you want to be honest, avoid saying things that are critical of your child’s birth family; you don’t want them to internalize this negativity.

The behind-the-scenes story of an adoption isn’t always rosy—there’s sometimes a not-so-great reason your child wasn’t able to stay with their birth family. You don’t have to share all those hairy details just yet. But as your child matures and becomes more curious and confident, you can begin to add the more difficult nuances of the situation. “The rule of thumb is to [share] age-appropriate bits and pieces of the child’s story that don’t contradict the full story that you’ll eventually tell [them],” Mantell says.

Adoption will keep coming up, and often at times you least expect it—like when your child starts studying genetics at school. Agility is key, so don’t be thrown off guard by sudden questions; keep the lines of communication open and be ready for the topic to pop up quite randomly.

Make it clear that you’re open to these impromptu conversations, and proactively bring up the topic now and then to give your child the space to share any lingering concerns or questions. “Kids definitely think about it and may not know how to put their thoughts or feelings into words,” Mantell says. “They often really need to talk with their parents about their adoption fears and fantasies.”

Talking about adoption with your child is important, but so is actively listening. It’s your job to help them navigate their feelings and dispel any myths they’ve developed about their story. “Children can harbor fantasies that are more frightening than the truth—that birth parents will come back for them, reject them or are bad people…which can lead to anxiety and low self-esteem,” Mantell says.

Issues of abandonment can crop up in conjunction with adoption. “It’s human nature to want to be wanted,” Walfish says. "Most adopted children and adults come to ask the question, ‘Why did my mother give me up?’ While gentle, clear explanations help, it’s still an emotionally complex issue, she explains.

Some adopted children bring that fear of separation to their relationships. “When they get emotionally close, the stakes grow higher for risk of abandonment,” Walfish says. “In other words, the closer you get to someone, the more pain you can feel when they leave, which can stimulate early abandonment feelings.” Walfish suggests helping your child work through and process these mixed emotions. “Communication is the glue that holds relationships together,” she says.

Talking about adoption can be difficult for adoptive parents. If you’re feeling anxious, speak to a therapist, so you can be there for your child when they need you. “Parents should take their own anxieties very seriously and get education and/or therapy for their own fears of being rejected by the child,” Mantell says. You have to take care of yourself to be able to take care of your children.

About the experts:

Joni Mantell, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and director of the Infertility & Adoption Counseling Center in New York City.

Fran Walfish, PsyD, is a Beverly Hills family and relationship psychotherapist and the author of, The Self-Aware Parent.

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Plus, more from The Bump:

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.