Saying ‘No’ to Infertility Treatments

Each year, more than 4 million babies are born in the United States. Most of those pregnancies started the old-fashioned way, involving just two people and no hormone treatments or in vitro anything. But for one in eight couples, getting pregnant and carrying a baby to term only happens with medical intervention. And for a portion of them, it doesn’t happen at all.

Here are the stories of three women who faced infertility and decided against the treatments doctors said they’d need in order to ever realize their dreams of motherhood.

Making peace with "family of two"

Lisa Manterfield knew getting pregnant might be difficult. Her husband needed a vasectomy reversal, and there was no guarantee it would be successful. But when post-operative tests that showed that her husband’s sperm were up to the task, the eyes in her doctor’s office turned to her.

“Then we set off on another journey to figure out what was wrong with me,” says Lisa Manterfield, now 43, whose blog Life Without Baby inspired a book titled I’m Taking My Eggs and Going Home: How One Woman Dared to Say No to Motherhood. “Once it was clear that this was not going to be easy for us, it became absolutely all-consuming. It was really heartbreaking, too.”

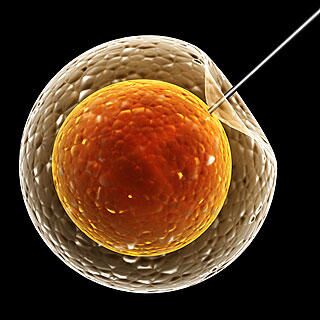

Manterfield, 34 when she first started trying to conceive, was diagnosed with poor ovarian function. Donor eggs were her only hope for pregnancy. After much deliberation, she and her husband decided against that treatment. “It had absolutely nothing to do with the genetic aspect of it,” says Manterfield. “It was more to do with the amount of drugs that I knew I would have to take.” She also considered the drugs the donor would have to take. Manterfield says she couldn’t in good conscious ask a young woman to do what she herself would not want to do.

Plus, while her husband completely supported Manterfield’s desire to be a mother, he had grown children of his own and so his zeal did not match hers. “He was doing it because I wanted to do it,” says Manterfield. “We agreed to take a break and take a step back and really reassess.”

After some research, Manterfield realized that even adoption was not the right course for them. This forced her to confront the loss of the baby she would never have.

“This is an intangible loss,” she says. “People don’t see it, they don’t recognize it, they don’t understand it,” says Manterfield. “If you’ve dreamed of having children, those children exist for you in your imagination. You’ve probably got names picked out and are imagining what life’s going to be like, what kind of a parent you’re going to be. A lot of women deal with this loss and that grief completely alone.”

Manterfield is now 43 years old and thanks to her stepdaughter, she’s a grandmother. She has accepted the concept of being a family of two. And while the glimmer of hope that a miracle could happen never goes away, she has accepted her life for what it is.

“At first it was ‘I am choosing this path and it’s going to have to be all right,’” Manterfield says. “It’s kind of ‘fake it ‘til you make it.’ And some time last year, I realized I’ve reached a point where even if somebody said, ‘You could have a baby tomorrow’ I wouldn’t do it. We have created a life and it’s a good life. I like the life that I have.”

Ending the pain of recurrent loss

When at age 19 Lisa Diamond still hadn’t started menstruating, her gynecologist told her she might never be able to get pregnant. The news didn’t really hit her until 18 years later when she actually did want to become a mother.

“I decided to pretend that the doctor never said it,” says Diamond of Oakland, Calif. “So I kept trying to get pregnant and eventually I did.”

But that pregnancy ended in miscarriage, as did her next two. Infertility specialists said her hormone levels were too low to support a pregnancy. Plus, as one doctor told her, she had “eggs as old as a 50-year-old’s.”

“I’m like, ‘Great, it’s my fault,’” Diamond says. “Then there was the self-blame. I shouldn’t have waited so long.” Doctors recommended in vitro fertilization. But Diamond couldn’t do it.

“It’s very invasive and very expensive and it ran a very true risk of having multiples,” says Diamond. “Kids are great, but I didn’t want twins and I certainly didn’t want triplets. And I’m a very pro-choice person but having lost babies, I knew that [selective reduction] was not a choice for me.”

So Diamond said no to fertility treatments. But saying no to interventions rarely means a woman is saying no to the dream. And so Diamond took a friend’s advice and visited a Chinese herbologist. She explained the miscarriages and was told to brew a foul-smelling batch of herbs into a tea.

“It tasted like boiled furniture,” says Diamond. “But this was my last thing. The trying was getting too painful. You pee on the stupid stick and it says you’re pregnant and then three weeks later you’re not. It just gets very, very upsetting. You can only go through that so many times.”

No one can say for certain whether the tea had any part of it, but that month, at the age of 41, Diamond got pregnant. And she stayed pregnant. Her daughter, Kyra, is now 6.

“We like to tell Kyra that she picked us,” says Diamond. “Not only did she ‘hold on tight’ during the pregnancy and not miscarry, but the doctors literally had to unwrap her arms and legs from my umbilical cord. She was clinging to it like a teddy bear.”

Choosing adoption

At age 31, married for a year and settled in her career as a lawyer, Lori Alper of Bedford, Mass., decided to start trying to get pregnant.

“I was trying to work and trying to conceive,” Alper says. “I was essentially a stressed-out basket case.”

For five years, month after month went by without the news Alper was desperate for. Meanwhile whenever a friend said she “had great news” she knew she had to mask her own disappointment. She saw babies everywhere — at the mall, in the park — and it only amped up her sense of desperation.

“You just get to the point where you want to have a baby and are willing to try anything to get there,” she says.

So when her doctor prescribed a drug to stimulate her ovaries to produce eggs, she swallowed her aversion to medication and started treatment. But it took an unbearable toll on her body.

“I just overall wasn’t feeling well,” she says. “I think my immune system was shot.”

The side effects were so intense that Alper decided not only to stop treatment, but to stop trying to conceive and instead pursue a domestic adoption. “It was a huge decision but a liberating one,” Alper says. “There are so many incredible ways to become a parent. We let go of infertility treatments to produce this baby that clearly nature wasn’t ready to give me.”

While waiting for their adopted son’s birth, Alper started taking care of herself both physically and mentally. She went for massages, practiced yoga and had acupuncture treatments to strengthen her immune system. Then her son was born, and her dream of motherhood was finally realized.

And eight months later, it was realized again when, without any intervention, Alper found herself pregnant for the first time. Two years after her second son was born, she gave birth again.

“I tell my oldest son all the time, ‘You’re the one who made me a mother,’” says Alper, whose boys are now 12, 11 and 9. “I tell my kids that each of us has our own story and whether it’s through adoption or through natural birth, it doesn’t really matter. It just brings us all together.”

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Plus, more from The Bump:

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.