How to Prevent Plagiocephaly (Aka Flat Head Syndrome)

You may not have heard the term plagiocephaly (that’s pronounced pley-jee-uh-SEF-uh-lee in case you were wondering), but you might have heard of flat head syndrome. “The word plagiocephaly actually just means ‘flat head,’” says Michael L. Cunningham, MD, PhD, medical director of Seattle Children’s Craniofacial Center and division chief of craniofacial medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine. So what is plagiocephaly, exactly? It’s an umbrella term used to describe an infant’s flat or deformed head shape, and while it sounds alarming, it’s usually pretty harmless. In fact, once baby starts to sit up, plagiocephaly often disappears on its own within months. Here’s what causes flat head syndrome and how to treat and even prevent it.

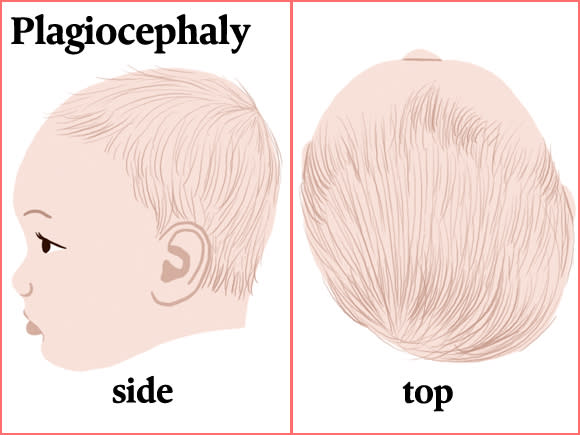

There are three types of plagiocephaly to know:

Positional plagiocephaly

This is the most common type of plagiocephaly and, as the name implies, it develops from the positioning of baby’s head, Cunningham explains. Infants tend to sleep with their head turned to either the left or right. Since a baby’s skull is extremely soft, consistent gentle pressure, like from repeatedly lying against a crib mattress, can give baby’s head an asymmetrical shape.

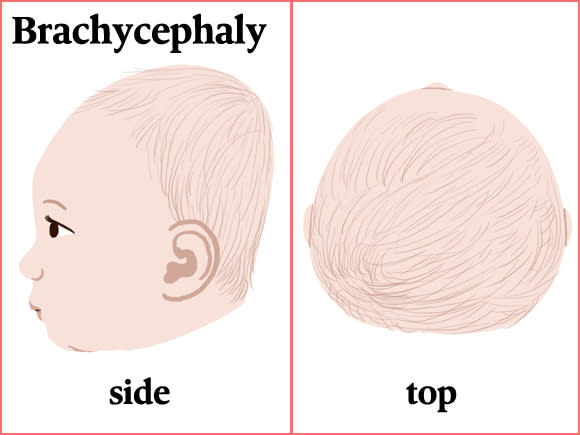

Brachycephaly (brack-ee-SEF-uh-lee)

This type of plagiocephaly happens when baby sleeps facing straight up, looking toward the ceiling, so the skull flattens on the very back instead of on either side of the head. “Really, the only difference between positional plagiocephaly and brachycephaly is where the flattening occurs, based on how the baby lies,” Cunningham says.

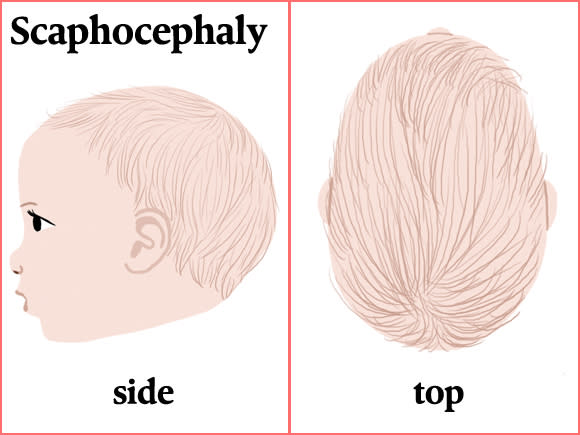

Scaphocephaly (skaf-o-SEF-aly)

Much less common but more serious than the others, scaphocephaly happens as the result of a birth defect when the joints between the bones of baby’s skull close up prematurely and prevent normal growth. “When you’re born, the top of your skull is made up of five bones,” Cunningham says. “In between the bones, there’s rubbery soft tissue that expands as your brain grows.” In scaphocephaly, the bone grows across the soft tissue, fusing two bones and restricting the growth of the skull. “The head gets very narrow because it can’t expand from side to side,” Cunningham says. When talking about scaphocephaly you may also hear the term craniosynostosis (kray-nee-o-sin-os-TOE-sis). Scaphocephaly is the most common type of craniosynostosis, which is a type of plagiocephaly.

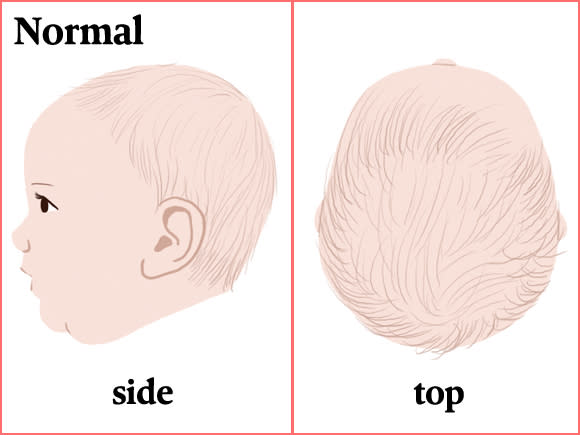

Normally, a healthy infant’s skull is perfectly round in the back and symmetrical on the left and right sides. If you’re concerned baby might have plagiocephaly, examine their skull and look for any asymmetric abnormalities or flat spots. You may also notice baby has less hair on one side or area of their head. Most pediatricians check for plagiocephaly during routine checkups, but it’s smart for you to flag it too, since one form—craniosynostosis—can have long-term effects. “Anytime a parent notices that the back of the skull is looking asymmetric, they should bring it up with their doctor,” Cunningham says.

Pressure against baby’s soft skull can change its shape, just like a ball of Silly Putty will flatten out on the bottom after you leave it on the table for a while. Most plagiocephaly cases can be traced back to the following:

Sleep position

In 1994, the American Academy of Pediatrics launched the Back to Sleep campaign to encourage parents to put babies on their backs to sleep. This simple move cut the rate of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome by more than 50 percent, saving thousands of babies lives—but it drastically increased the number of cases of flat head syndrome. “The nature of back-sleeping has the baby lying in a more static position than stomach-sleeping,” Cunningham says. “So these infants are at a greater risk of developing flattening.” Of course, since there are ways to prevent plagiocephaly, you don’t want to stop putting baby to sleep on their back.

Too much time in swings, bouncers and car seats

“Anything that makes baby’s head flop to one side isn’t good,” Cunningham says. That goes for most swings and bouncers, so it’s best to minimize the amount of time you use them daily. “You’ve seen babies in car seat carriers, right? They’re all scrunched over,” he adds. Car seats are a must though, so look for one that’s the right size for baby, and, if necessary, use the infant insert that keeps baby’s head in a more neutral position. “I know it’s hard to do, but I also tell parents: when you come back from the grocery store with baby and they’re sound asleep in their car seat carrier, you’ve got to take them out and place them in their crib,” he says.

Prematurity

Very premature infants, whose skulls are even softer than full-term babies, can develop a unique kind of plagiocephaly. “They’re so ‘floppy’ that they lie with their heads rotated 45 degrees to one side or another, so their skull flattens along the sides and they get these really long, narrow heads,” Cunningham says. Plagiocephaly is also common in multiples, likely because they’re crowded in utero with their soft, little skulls pressed up against one another, he adds.

Torticollis

Also called wryneck or “twisted neck,” torticollis happens when the neck muscles force the head to turn or rotate to the side. There are a couple different kinds of torticollis, Cunningham says. The neck muscles can be injured at the time of birth, or sometimes baby can favor one head position and limit the development of other muscles. “Because they always hold their neck in that way, one muscle doesn’t get as long, so they induce torticollis,” he says. “I refer to it as secondary torticollis because babies don’t start out with any kind of problem—they cause it by always sleeping in one position and reducing their range of motion.”

With the exception of craniosynostosis, which restricts brain growth, plagiocephaly is usually temporary and typically doesn’t cause problems; the brain continues to grow normally, just in a different shape. Still, many parents would prefer to avoid plagiocephaly if possible.

Luckily that’s very easy to do. The number one way to prevent flat head syndrome? “Don’t leave your infant in the same position all the time,” Cunningham says. If baby tends to always look to one side while sleeping—likely in the direction where the interesting things are—reverse their position in the crib each night (place their head where their feet usually go), so they have to look the opposite way. Or if you have a cool mobile or toy within eyesight, move it to the other side of the crib to refocus baby’s gaze. “Be aware of positional preferences that baby has so you can rotate them as needed,” Cunningham says.

The second most important practice for plagiocephaly prevention is to make sure that when baby is awake, they’re not always on their back. Practice tummy time each day to help prevent plagiocephaly and help baby start preparing for other milestones like rolling over and sitting up. “A baby lying on their stomach won’t face-plant on the rug,” Cunningham says. “They’ll lift their head up so it’s in a neutral position while also strengthening their neck muscles.” The easy rule: If baby’s awake, flip ’em over.

While plagiocephaly pillows are available for sale—they have a rounded divot in the center to reduce pressure on baby’s skull—Cunningham doesn’t recommend them. The National Institutes of Health also advises against placing any pillows or other soft objects in baby’s sleep area, as this can be a SIDS risk.

Expert recommendations for treating flat head syndrome sound a lot like their suggestions for preventing it: Repositional therapy involves preventing baby from resting on the flattened spot all the time. Trick baby into turning their head the other way at bedtime or during naps, and put baby on their belly whenever they’re awake and supervised (meaning, the more tummy time, the better). “Just keep them off the back of their head as much as you can,” Cunningham says.

If baby has asymmetric neck muscles, your pediatrician might recommend physical therapy to strengthen those muscles and improve range of motion. Or your doctor might just show you some exercises you can practice at home.

Cranial orthotic therapy with a baby helmet

If you’ve ever seen a baby wearing what looks like a mini skateboard helmet, you’ll know what this is. Cranial orthotic therapy is another treatment your doctor might suggest for fixing flat head syndrome. How it works is pretty simple: “It’s like growing an apple in a bottle,” Cunningham explains. As baby’s brain grows and pushes out against the skull, the pressure of the helmet helps force the bones, and therefore baby’s head, to grow into the more normal shape the helmet provides. A baby’s skull stays very malleable for quite a while (helmet treatment usually starts between 4 and 6 months), and it doesn’t take much pressure to remodel the skull; remember, it was a soft crib mattress that likely created the flat spots in the first place.

There are no hard-and-fast rules for who will benefit from cranial orthotic therapy, but baby helmets are typically reserved for extreme cases. “If we see a baby who has such significant asymmetry or abnormality in their head shape that I’m concerned it’s going to be a psycho-social problem for that child when they grow up, I’ll recommend a helmet,” he says. “If I see a baby that has very mild head shape differences but the family’s concerned about it, I don’t recommend doing helmet therapy because I don’t think the baby is going to get any benefit.”

A study published in 2014 also discourages helmet therapy for healthy infants with moderate to severe skull deformation. And that should be a relief for most parents, given that the treatment averages around $2,000 per helmet and baby usually has to wear it up to 23 hours a day for three to six months. When in doubt, talk to your pediatrician about what’s best for baby.

Expert bio:

Michael L. Cunningham, MD, PhD, is chief of the division of craniofacial medicine and professor of pediatrics in the department of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He is also the medical director of the Craniofacial Center at Seattle Children’s hospital, where he has been on staff since 1991, and holds the Jean Renny Endowed Chair in Craniofacial Medicine.

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.